At first glance, almshouses are an anachronism, often dainty, charming cottages placed nonchalantly among the bustle of modern cities. The vast majority are registered charities that provide accommodation to older adults at discounted rates, but some also provide free accommodation with additional services, allowances and gifts.

Almshouses are a historic institution, having existed in England and Wales since the 10th century, but are now experiencing what the Times has described as a “boom”. Other newspapers have proposed almshouses as “the solution to ageing Britain”. They highlight that over the last two years, 712 new almshouses have either been built, bought, or are currently under construction. Today, 1,600 almshouse charities support over 35,000 residents.

An article in The Guardian reported almshouses as providing a proven model for both social policy and effective philanthropy. Counterintuitively, almshouses are presented as a modern progressive solution; a radical approach to tackling issues of social isolation and the marginalisation of an ageing society. The article calls on housing developers to provide “almshouse-style” accommodation in new developments.

The almshouse resurgence is filling a gap in provision but it’s worth considering why such a gap exists. The need for almshouses are, after all, the symptom of a bigger problem. One reason for their establishment in the middle ages was a lack of alternative welfare provision; they prevented poor older people from falling into vagrancy. Almshouses, as many charities are, are products of necessity and the consequence of inequality.

Charities are not solutions to problems: they are red flags that something is systemically wrong.

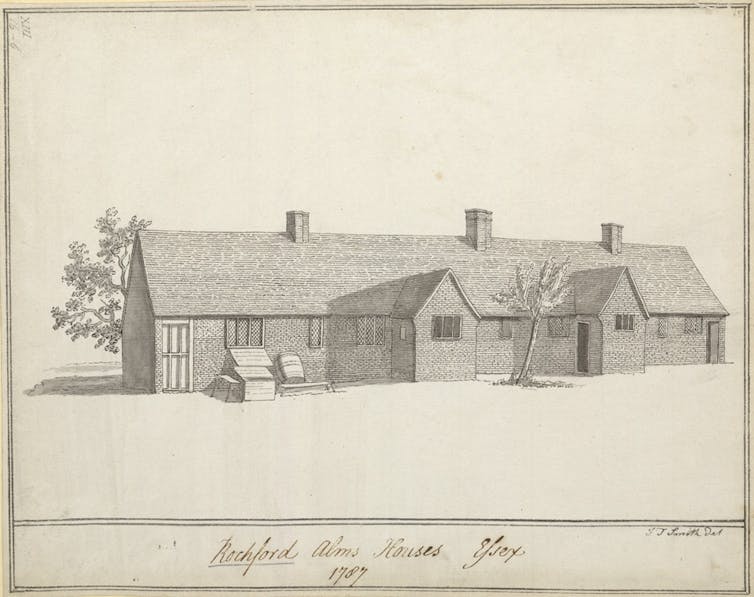

Illustration of Rochford Almshouses in Essex, 1787. Image: The British Library.

Red flags

The ONS estimates that the proportion of people aged over 85 in the UK is expected to double over the next 25 years, putting enormous strain on health and social care systems.

Coupled with this, income and health inequalities are becoming more acute, while services and support for older people, often poorly funded by the public purse, have faced significant financial constraints. Inequalities tend to compound over time, the effects of cumulative disadvantage over the life course taking their toll in terms of health, housing and mortality. As a result, inequality is rife in later life.

In the UK, the top 20 per cent of people aged between 66 and 85 have a household income of double the bottom 20 per cent. At the very bottom of society, many older people are falling through the safety net of state provision. Federated charities such as AgeUK, and philanthropic networks such as the Community Foundation, are able to provide research, funding and support on a national scale but are subject to significant pressures.

The almshouse resurgence is filling a gap in provision. But while this is commendable, it’s not clear if they are the answer. Almshouses have offered respite out of necessity for ten centuries: they are less of a panacea and more symbolic of a lack of attention to vulnerability in older people.

Selective protocol

Almshouses were originally established by local landowners or clergy to provide respite for ageing churchmen. Admittance later expanded to embrace pious individuals who shared the faith, or other beliefs of the philanthropist, or who happened to live on the estate, in the parish, of a benevolent philanthropist.

Today, they still bear the marks of these origins, with trustees obliged to fulfil the wishes of the benefactor, no matter how incompatible with modern Britain. The eligibility criteria for entry to almshouses are often laid out in the deed of trust of each individual almshouse as stipulated in will of the benefactor. Although over time many of these requirements have been reformed by trustees, some still skirt on the edge of discrimination.

A document connected with the foundation of Henry VII’s almshouses at Westminster. Image: National Archives UK.

Trustees make the decisions regarding who can or cannot not obtain access to reduced rents. Crucially, these decisions are not always based on need. They may be based of variety of other factors, such as the religious persuasions of applicants, whether they reside in particular parishes or areas, or even whether they are of “good character”. Until the late 1970s, for example, the Worshipful Company of Weavers Almshouses provided accommodation solely for widows of Freemen of the Weavers. Such old-fashioned requirements are becoming increasingly rare, as trustees use their discretion when filtering applications. But almshouses still reserve the right to be selective; the state does not.

The reason for the longevity of many almshouses is intimately tied to their financial models. Often relying on ancient endowments, almshouses are subject to strict financial schemes which have been highly resilient to economic change. In many cases the objective was to ensure the wishes of the benefactor were carried out in perpetuity. Such endowments are incredible assets that the overwhelming majority of charities are, sadly, unable to rely on.

A 2018 CityMetric article alluded to the problem that this historic model of funding creates. Until recently, almshouses were often established on the basis of conditional philanthropy to the deserving poor. This is an idea that is quite simply incompatible with modern Britain – even with the best of intentions, boards of trustees, who often suffer from a lack of diversity, are not best placed to make such universally important decisions.

The future

In the absence of large scale benefactions, the kind of which took place hundreds of years ago, new financial models need to develop.

Unlike France and Canada, the UK has no dedicated resource to support the development of the social innovations that are required to meet the challenges of later life. But there is a great deal of potential for shared cooperative finance, such as that being developed by the coop InvestAge (which one of the authors co-founded) to fund innovative and socially connected housing. InvestAge wants to see a world where people can live with greater autonomy in later life. After all, creating a better old age for all is in everybody’s best interest.

The burgeoning number of almshouses are a broader reflection of the state’s failure to look after some of the most elderly and vulnerable people in society. Innovative new solutions are urgently needed.

![]()

Michael Price, Senior Research Fellow, University of Leeds and Victor Harlow, PhD Candidate in Education History, Newcastle University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.