Standing in the middle of a usually busy central London street during Extinction Rebellion’s protests, the air noticeably cleaner, the area quieter, I was struck by the enormity of the challenge ahead of us. We need to create a transport system that is zero carbon in only a few years. Despite London’s Ultra Low Emission Zone, the daily reality is still toxic traffic fumes, unjustifiable road deaths and high levels of transport carbon emissions (up to one-third of all emissions in many places). There are over 9,000 extra deaths a year in London due to illegal air toxicity, much of which is from road transport.

But some cities have created more car-free, healthy and safe places. Copenhagen and Amsterdam are known for their amazing cycling culture. Curitiba, in Brazil, has an amazing bus transit system that functions like a subway network. Helsinki has committed to going car-free as soon as possible. Tokyo has some of the lowest levels of car ownership in the world. And Venice hasn’t seen a car in its history.

As I’ve shown in my latest book, creating the car-free city is possible, and urgently necessary, right now. We have all the technical and policy know-how. But we lack a vision of how it could be different, and the recognition that far from a sacrifice, it will bring mainly improvements, rather than constraints, to our lives. Such visions are necessary. The best way to demonstrate this is by using a bit of speculative fiction. So bear with me while we jump into an imagined near future.

What 2025 could look like

After the government capitulated to mass public unrest in 2020, citizen’s assemblies met to plan the future of the country. One of them outlined what they called “The Great Transport Turning”, an ambitious new mobility plan for the country that would unlock us from the car and create beautiful, safe and clean places for people. I can’t believe it’s only been five years, but our neighbourhoods have been completely transformed into beautiful, clean, safe places for everyone. I see my kids smiling every day as they safely rush off on their bikes and scooters to meet friends or go to school.

So how did it all happen? On the recommendation of the People’s Assembly, the Department for Transport was renamed the Department for People’s Mobility. It was given a remit to implement a “climate safe and socially just mobility plan” by 2025. It cost around £300bn – about a third of the total cost of the UK’s transition to zero carbon – funded by a combination of a windfall from closing tax avoidance loop holes, a hike in corporation tax, and a citizen’s transport levy.

An army of newly trained people’s mobility officers started to implement the people’s plan. The UK’s big cities got a huge makeover, with dozens more suburban train stations and extensive electrified mass transit networks comprising trolley buses and trams that were connected to surrounding small towns. That took a huge slug of cars off the roads straight away. Even though it’s not all quite finished, enormous progress has been made towards creating a zero carbon transport infrastructure, along with a green jobs bonanza in the construction industry.

Regional co-operatives, owned and managed by workers and users, were set up to run it all. Across the UK, everyone gets 14 free tickets each week, with any extra journeys costing a flat rate of just a £1 for travel within their locality. Employee-owned bus companies with fully electric fleets, cycle storage on the front and more access for wheelchair users than current buses, were set up.

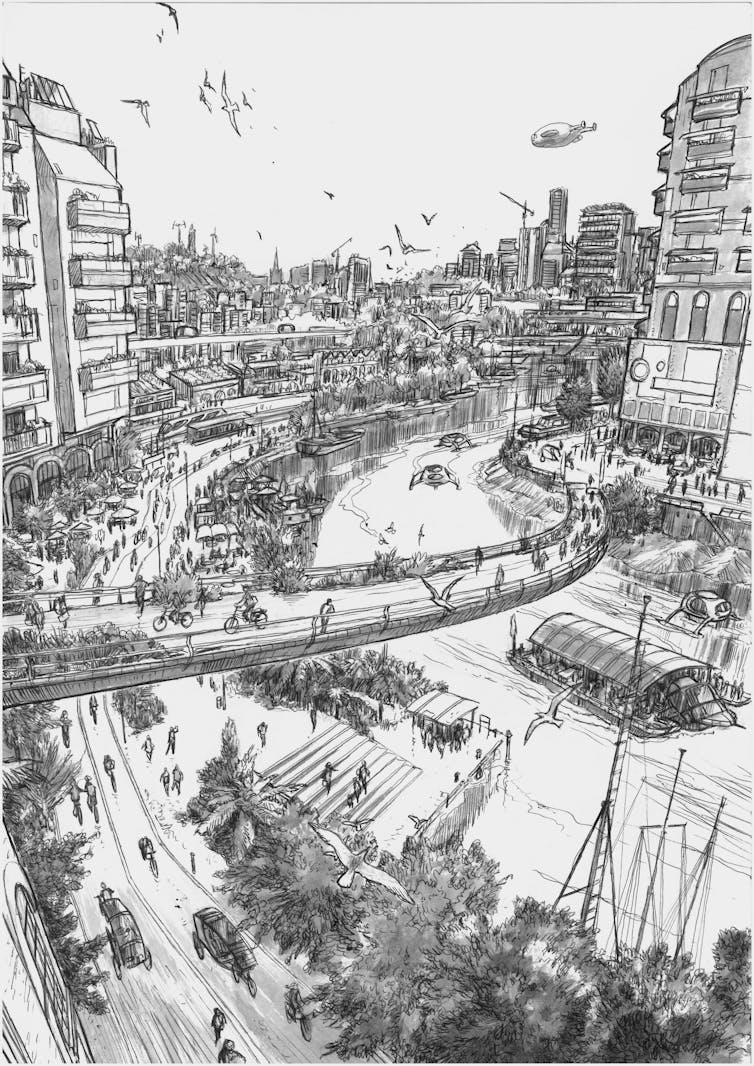

Car-free city. Image: © James McKay.

Once public transport was working properly, diesel and petrol cars were banned in urban areas. The UK went from a car owning nation, with about 40m cars, to around a million – in just five years. The old ones were sent back to the corporations that made them under new circular economy legislation. Free electric shared taxis were introduced for people with mobility issues and shared electric mini-buses for long distances or rural connections.

But the biggest change is to the reasons we move around. School days have been shortened, allowing all schools and universities to undertake community-based climate action sessions. All workplaces stagger their starting times to avoid congestion spikes and rush hour, and the Citizen’s Income means most people have gone part-time and travel less anyway. The 20-minute neighbourhood idea was introduced, meaning that within cities all basic goods and services needed for a good daily life are never any more than a 20-minute walk away; and for those with mobility issues, community minibuses constantly circulate.

Neighbourhoods look and feel completely different. Some roads remain, reclassified as service roads for buses, trams, or for electric vehicles for trade or health workers. But all other roads are now neighbourhood mobility routes. Two lanes have been reduced to one, creating active travel corridors for walking and cycling.

Street skate part. Image: kjbax/Flickr/creative commons.

In the space freed up, life and activity flourishes. Independent traders, community businesses, green spaces, pocket parks, micro gardening, allotments and playgrounds have appeared like mushrooms. The noise of traffic has been replaced by the constant hubbub of laughing, playing and chatting. Nature and wildlife have found ways back in through biodiversity corridors. All urban areas now have a 20mph limit, which has reduced road deaths and serious injuries by nearly a half.

Micro-mobility hubs are found at intersections. Owned by each neighbourhood and accessed through a flat monthly fee, there is a stock of electric mobility scooters, bikes, trailers, Dutch-style box bikes, and e-scooters. Families can pop down and grab a selection and go off for the day around the city visiting parks, shops and museums.

In the city centre, multi-storey car parks have been turned into bike racing tracks and rooftop gardens. Along all dual carriageways, surplus lanes have been turned into sports pitches for football, cricket, rugby, cycling. The UK has become a healthy, sporting nation. Kids are no longer warehoused around in cars, stuck in front of video games, or entertained in corporate suburban retail parks. They are free, happy and healthy, playing in the roads that used to kill, maim, poison and pollute.

Kids play on bikes at Lilac co-housing community, Leeds. Image: © Paul Chatterton/author provided.

This massive shift hasn’t been anti-car. Our need for the car just evaporated. And with the end of auto advertising, we stopped wanting them. People look back and wonder why we were so obsessed with them. And for those still addicted to cars, community racing tracks have been set up so people can get their speed and adrenaline fix.

Back to 2019

From the perspective of today’s polluted and dangerous streets, this vision of the near future may seem like a pipe dream. But in fact it’s a collection of examples that are already happening somewhere in the world, or research ideas that, with political will and financial incentives, could be implemented.

And what’s not to love? The effects of such a transportation revolution would be incredible. There would be thousands less deaths or serious injuries from traffic accidents, respiratory and coronary diseases every year, reduced depression and social isolation, and an increase in independent traders and a more vibrant local economy. We would no longer have toxic illegal air, carbon emissions from transport would be practically zero and everyone would be able to get around where they live regardless of how rich or poor they are.

It would also drastically help rebuild communities. People would be less lonely, out and about rather than sitting in private vehicles. People would talk more and figure stuff out face to face. Tackling carbon emissions in transport genuinely is a win-win situation.

Getting there won’t be easy. It will require a strong citizen’s movement on the streets, as well as in committee meetings, court rooms and research centres. We will need officials, elected representatives, business leaders, inventors and researchers to become activists and rebel against the current transport status quo.

Time is short to get transport emissions and toxic air under control. But the benefits that transforming transport in this way could offer are huge. We must not miss this moment.

Paul Chatterton, Professor of Urban Futures, University of Leeds.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.