Urban planners, governments and developers are increasingly interested in making cities “liveable”. But what features contribute to liveability? Which areas in cities are the least and most liveable? The various liveability rankings – where Australia tends to do quite well – don’t provide much useful guidance.

In a recently released report, Creating Liveable Cities in Australia, our team defined and produced the first baseline measure of liveability in Australia’s capital cities.

We broke down liveability into seven “domains”: walkability, public transport, public open space, housing affordability, employment, the food environment, and the alcohol environment. This definition is based on what we found to be critical factors for creating liveable, sustainable and healthy communities.

Each of the liveability domains is linked by evidence to health and wellbeing outcomes. They are also measurable at the individual house, suburb and city level. This means we can compare areas within and between cities.

While all seven domains are important, three are explored here in more detail.

Walkability

Urban planning that encourages walking is crucial for liveable cities. Image: Julianna Rozek/Author provided.

In liveable cities, streets and neighbourhoods are designed to encourage walking instead of driving. Homes, jobs, shops, schools and other everyday destinations are within easy walking distance of each other. The street network is convenient for pedestrians, with high-quality footpaths, short blocks, few cul-de-sacs and higher-density housing.

Walkability is an important factor in liveability because it promotes active forms of transport. Increasingly physically inactive and sedentary lifestyles are a global health problem, and contribute to around 3.2m preventable deaths a year. In Australia, 60 per cent of adults and 70 per cent of children and adolescents do not get enough exercise.

We measured walkability using a combination of features that are linked to health benefits. Our “walkability index” included housing density, access to everyday destinations and street connectivity within 1,600m of a residence. This is a commonly used “walkable” distance, equivalent to about 20 minutes’ walk, and features within this affect how likely a person is to walk.

However, walkable neighbourhoods achieve their full potential only when residents have easy access to employment – particularly by public transport.

Public transport

Liveable cities promote public transport use instead of driving. Most homes are within easy walking distance of transport stops, and services are frequent enough to be convenient.

Good access to public transport supports community health in two ways: by encouraging walking and by reducing dependence on driving.

Australian cities have largely been designed for cars, at the cost of community health. Each hour spent driving can increase a person’s risk of obesity by around 6 per cent. Road-traffic accidents are the eighth-leading cause of death and disability globally, and one of the leading causes of death in Australians up to the age of 44.

Cars are also a major source of urban air pollution and noise, which are harmful to mental and physical health.

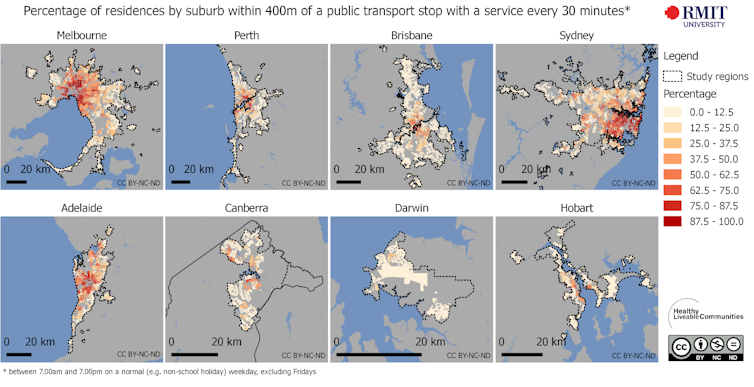

In previous work, our team found that people were more likely to walk for transport if they had a public transport stop within 400m of their home. The service frequency was also important – it needed to be least every 30 minutes on a normal weekday.

In Creating Liveable Cities in Australia we used this combined measure to map the percentage of homes in a suburb, local government area, or city with close access to frequent public transport.

Creating Liveable Cities in Australia.

Public open space

In liveable communities, most people live within walking distance of a green, publicly accessible open space such as a park, playground or reserve.

Green space has many physical and mental health benefits for people, and social and environmental benefits for communities. Parks provide opportunities for physical activity, such as jogging, ball sports and dog walking.

Increasingly, research is finding clear links between living in neighbourhoods with lots of parks and higher physical activity.

Urban green spaces are also important for plants and animals displaced by urban development and provide other environmental benefits. The cooling effect of trees and green spaces can play an important part in maintaining the liveability of Australian cities, particularly as heatwaves in Melbourne and Sydney are likely to reach 50°C by 2040.

In soon-to-be-published work, having access to a public open space within 400 metres (about a five-minute walk) of at least 1.5 hectares in area was associated with recreational walking.

For this report, we struggled to find a dataset of public open space that was consistent and available nationally. Some areas have high-quality data available from previous research projects or local councils, and satellite imagery provides useful information about tree cover.

However, national data standards are needed to enable cities to benchmark and monitor their progress in meeting liveability targets.

The liveable city is greater than the sum of its parts

The phrase “liveable city” conjures up a vision of leafy streets, happy residents walking, cycling or catching public transport, and children playing in neighbourhood parks. This image, while inspiring, is not useful for urban planners and governments who are working to make cities more liveable.

Distilling liveability into seven domains, which can be measured and are linked to health and wellbeing outcomes, provides policymakers and practitioners with what they need to ensure we maintain and enhance the liveability of our cities as they grow.

![]() You can hear more from researchers involved in Creating Liveable Cities in Australia at the Designing Healthy Liveable Cities Conference on 19-20 October in Melbourne. It’s being hosted by the NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence in Healthy Liveable Communities and you can register here.

You can hear more from researchers involved in Creating Liveable Cities in Australia at the Designing Healthy Liveable Cities Conference on 19-20 October in Melbourne. It’s being hosted by the NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence in Healthy Liveable Communities and you can register here.

Julianna Rozek is a research officer and Billie Giles-Corti, director of the Healthy Liveable Cities Group at RMIT University.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.