In the game of rock, paper, scissors, paper is more powerful than rock. And so it was in the second half of the 19th century, when influential local newspapers shifted stones, bricks and mortar to build the townscapes that endure to this day.

Around the British Isles, and across the world, purpose built newspaper offices towered over main streets and market squares – at the heart of of the towns and cities they served. In the UK they became an increasingly common sight from the 1860s onwards, when the end of newspaper taxation led to a boom in local publishing.

At the same time, they had an effect on the construction of other public buildings. The act of reading newspapers was considered so important that the biggest room in new public libraries was designed and built specifically for this purpose.

Today, as print circulation and profits fall, local papers are abandoning town centres. Many are selling their landmark buildings and moving to cheaper premises in the suburbs, while some reporters do their work from cafes.

In November 2018, the Bath Chronicle gave up its shopfront home and moved into offices inside a local college. Earlier in the year, the Swindon Advertiser moved more than two miles to a building out of town.

Like redundant churches, these empty or converted buildings are a sign of social change. The Scotsman’s landmark building on North Bridge, Edinburgh, is now a hotel. What was once the home of the Blackburn Times is now a pub.

The Blackburn Times they are a changing. Image: author provided.

In the mid-19th century, local newspapers were a far more popular product than they are today. When the gentlemen of Preston, in the north of England, decided to build their own club premises in a Georgian square in 1846, they made sure that the largest room in the building was the one for reading the news.

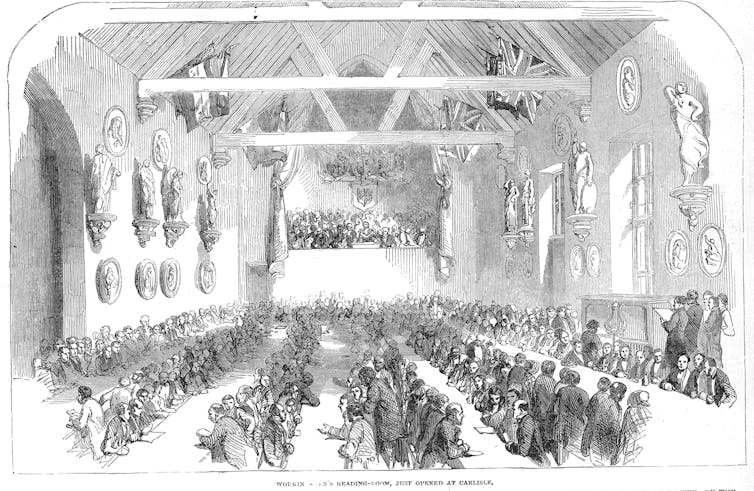

Working class men were equally keen. In 1851, a group of Carlisle newspaper readers attracted national attention when they opened a purpose-built news room. By 1861, Carlisle had six working-class reading rooms, with around 1,000 members.

Carlisle reading room. Image: UCLAN/author provided.

The design and use of pubs was also influenced by the Victorian newspaper. A sign in the “news room” of Liverpool’s Lion Tavern is still there today, demonstrating how pubs saw the availability of newspapers as an attraction worth advertising.

Landlords even paid skilled public readers to bring the newspaper alive in crowded pubs with readings. One Liverpool licensee, John McArdle, “performed” the paper himself, with Irish nationalists coming to his pub in Crosbie Street every Sunday night to hear him read from The Nation.

Building an industry

From the 1850s, when taxes on newspapers were abolished, local papers overtook London papers in sales and readership, as my new book recounts. It was then that booming provincial newspapers began to carve their names in stone, literally, with purpose built offices, proclaiming their importance to the local economy and culture.

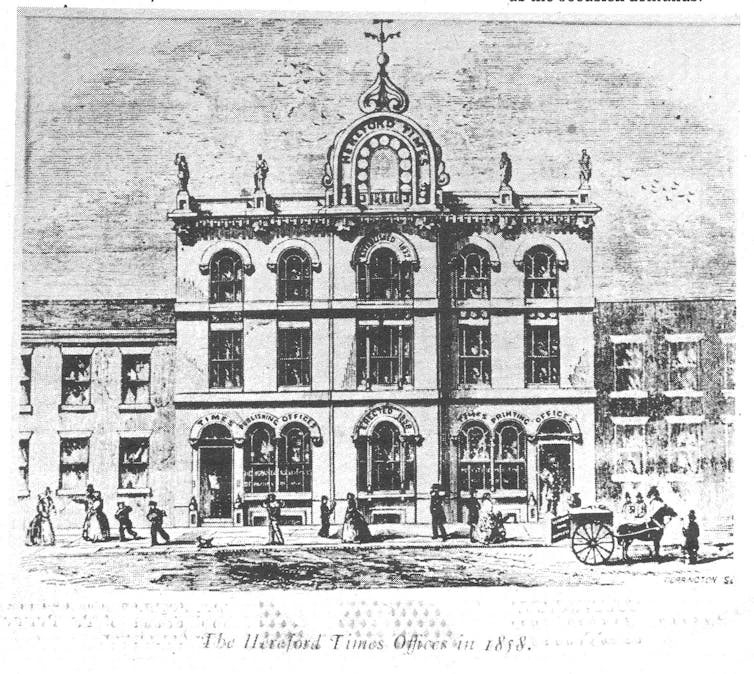

One of the first was built by the Hereford Times in 1858. It was in an Italian style with elaborate scrollwork, roof line statues and an ornate cupola, engraved with the newspaper’s title. Such pretentious classical elements were also used by The Times in London. As media historian Carole O’Reilly wrote, this was the architectural language of “power, wealth, authority and taste”. Statues of the pioneering printers Gutenberg and Caxton were common, as were town crests, proclaiming local identity.

The 1858 home of the Hereford Times. Image: author provided.

Newspapers’ place at the centre of the town symbolised their place in readers’ lives. In the front office, people queued to announce rites of passage in the local paper – births, marriages and deaths – or to consult the fullest archive of local life, the bound back copies of the newspaper.

Another type of landmark building, the public library, would have been much smaller if Victorian newspapers had not been so popular. News rooms were specifically mentioned in the 1850 Public Libraries Act which started the growth of public libraries. Magazines and newspapers were more popular than books, and so were given more space by architects and early librarians. The manual on how to run these new institutions suggested giving half of the public area to newspapers.

Newspaper popularity also meant a place was needed where you could buy them, and the newsagent shop arrived in the 1860s, adding a messy but popular new look to the streets, with shocking front-page images in the windows and jumbles of billboards on the shop front outside.

Today, those newsagents, libraries, pubs, and of course the newspapers themselves, are all in decline. But the legacy of their boom time in the Victorian era remains – in the architecture and buildings of the towns and cities whose inhabitants once placed enormous value on their local news.

![]()

Andrew Hobbs, Senior Lecturer in Journalism, University of Central Lancashire.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.