Less than four months after President Donald Trump pledged in his State of the Union Address to “rebuild our crumbling infrastructure,” prospects look dim. The Trump administration is asking Congress for ideas about how to fund trillions of dollars in improvements that experts say are needed. Some Democrats want to reverse newly enacted tax cuts to fund repairs – an unlikely strategy as long as Republicans control Congress.

Deciding how to fund investments on this scale is primarily a job for elected officials, but research can help set priorities. Our current work focuses on transit, which is critical to health and economic development, since it connects people with jobs, services and recreational opportunities.

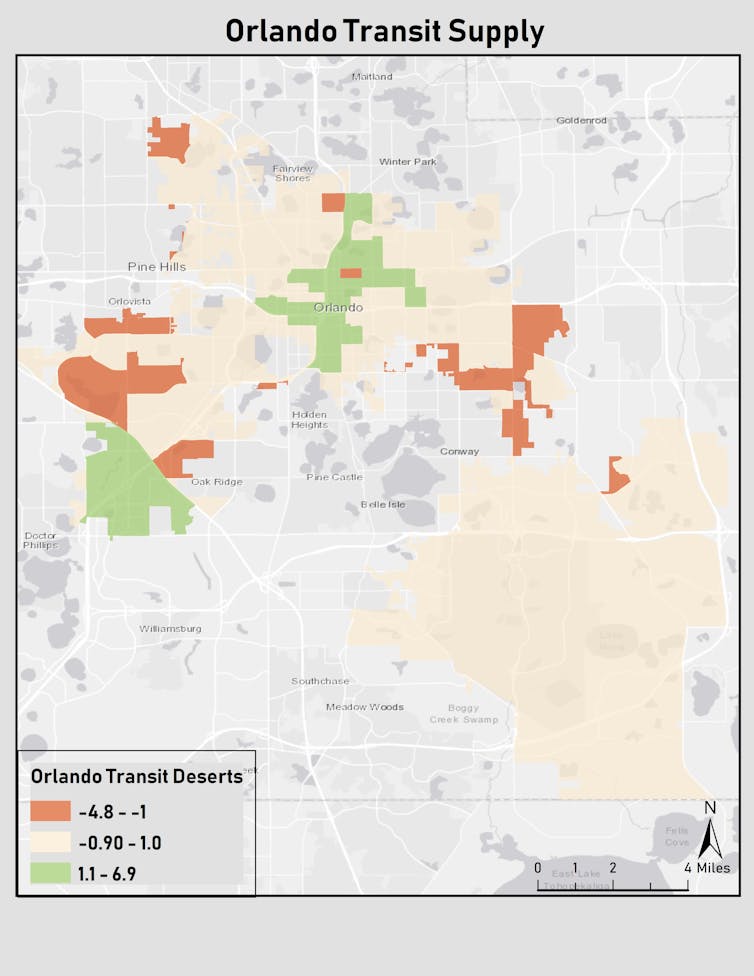

Along with other colleagues at the Urban Information Lab at the University of Texas, we have developed a website showing which areas in major U.S. cities do not have sufficient alternatives to car ownership. Using these methods, we have determined that lack of transit access is a widespread problem. In some of the most severely affected cities, 1 in 8 residents lives in what we refer to as transit deserts.

Deserts and oases

Using GIS-based mapping technology, we recently assessed 52 U.S. cities, from large metropolises like New York City and Los Angeles to smaller cities such as Wichita. We systematically analysed transportation and demand at the block group level – essentially, by neighborhoods. Then we classified block groups as “transit deserts,” with inadequate transportation services compared to demand; “transit oases,” with more transportation services than demand; and areas where transit supply meets demand.

To calculate the supply, we mapped out cities’ transportation systems using publicly available data sets, including General Transit Feed Specification data. GTFS data sets are published by transit service companies and provide detailed information about their transit systems, such as route information, frequency of service and locations of stops.

We calculated demand for transit using American Community Survey data from the U.S. Census Bureau. Transportation demand is difficult to quantify, so we used the number of transit-dependent people in each city as a proxy. A transit-dependent person is someone over the age of 12 who may need access to transportation but cannot or does not drive because he or she is too young, is disabled, is too poor to own a vehicle or chooses not to own a car.

Transportation deserts were present to varying degrees in all 52 cities in our study. In transit desert block groups, on average, about 43 per cent of residents were transit dependent. But surprisingly, even in block groups that have enough transit service to meet demand, 38 per cent of the population was transit dependent. This tells us that there is broad need for alternatives to individual car ownership.

Transit deserts in Orlando, Florida. Red areas are transit deserts, and green areas are transit oasis areas. In tan areas, transit supply and demand are in balance. Image: Urban Information Lab, University of Texas – Austin/creative commons.

For example, we found that 22 per cent of block groups in San Francisco were transit deserts. This does not mean that transit supply is weak within San Francisco. Rather, transit demand is high because many residents do not own cars or cannot drive, and in some neighborhoods, this demand is not being met.

In contrast, the city of San Jose, California, has a high rate of car ownership and consequently a low rate of transit demand. And the city’s transit supply is relatively good, so we only found 2 per cent of block groups that were transit deserts.

Who do transit agencies serve?

Traditional transit planning is primarily focused on easing commute times into central business districts, not on providing adequate transportation within residential areas. Our preliminary analysis showed that lack of transit access was correlated with living in denser areas. For example, in New York City there are transit deserts along the the Upper West and Upper East sides, which are high-density residential areas but do not have enough transit options to meet residents’ needs.

Our finding that denser areas tend to be underserved suggests that cities will be increasingly challenged to provide transit access in the coming decades. The United Nations estimates that two-thirds of the world’s population will live in cities by 2050, which will mean growing demand for transit. Moreover, fewer Americans, particularly millennials, are choosing to own vehicles or even get driver’s licenses.

This dual challenge underlines the urgency of investing in transportation infrastructure. The problem of transportation access is only likely to grow more acute in the coming years, and new infrastructure projects take many years to plan, finance and complete.

Expanding New York City’s bike lanes has given commuters an alternative to the deteriorating subway system.

Transit deserts reinforce inequality

We also found that relatively well-off neighborhoods have better transport services. This is not surprising: Wealthier people tend to have higher access to cars, and thus rely less on public transit.

Lower access to transportation for poorer Americans creates a kind of negative economic feedback loop. People need access to high-quality transportation in order to find and retain better jobs. Indeed, several studies have shown that transit access is one the most critical factors in determining upward mobility. Poor Americans are likely to have lower-than-average access to transit, but often are unable to move out of poverty because of this lack of transit. Investing in infrastructure thus is a way of increasing social and economic equality.

What state and city governments can do

Shrinking transit deserts does not necessarily require wholesale construction of new transit infrastructure. Some solutions can be implemented relatively cheaply and easily.

New and emerging technologies can provide flexible alternatives to traditional public transportation or even enhance regular public transit. Examples include services from transit network companies, such as Uber’s Pool and Express Pool and Lyft’s Line; traditional or dockless bike sharing services, such as Mobike and Ofo; and microtransit services like Didi Bus and Ford’s Chariot. However, cities will have to work with private companies that offer these services to ensure they are accessible to all residents.

Cities can also take steps to ensure their current transit systems are well-balanced and shift some resources from overserved areas to neighborhoods that are underserved. And modest investments can make a difference. For example, adjusting transit signals to give buses preference at intersections can make bus service more reliable by helping them stay on schedule.

Ultimately federal, state and city agencies must work together to ensure an equitable distribution of transportation so that all citizens can fully participate in civil society. Identifying transit gaps is a first step toward solving this issue.

![]() Junfeng Jiao, Assistant Professor of Community and Regional Planning and Director, Urban Information Lab, University of Texas at Austin and Chris Bischak, Masters of Community and Regional Planning Candidate, University of Texas at Austin.

Junfeng Jiao, Assistant Professor of Community and Regional Planning and Director, Urban Information Lab, University of Texas at Austin and Chris Bischak, Masters of Community and Regional Planning Candidate, University of Texas at Austin.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.