Despite almost universal scientific consensus that climate change poses a growing threat, President Donald Trump’s recent infrastructure plan makes no mention of the need to build resilience to rising global temperatures. Instead, it actually seeks to weaken environmental reviews as a way of speeding up the infrastructure permitting process.

This proposal flies in the face of scientific evidence on climate change. It also contradicts the priorities of many local leaders who view climate change as a growing concern.

During the summer of 2017, we and Boston University’s Initiative on Cities asked a nationally representative sample of 115 U.S. mayors about climate change as part of the annual Menino Survey of Mayors. Mayors overwhelmingly believe that climate change is a result of human activities. Only 16 per cent of those we polled attributed rising global temperatures to “natural changes in the environment that are not due to human activities.”

Perhaps even more strikingly, two-thirds of mayors agreed that cities should play a role in reducing the effects of climate change – even if it means making fiscal sacrifices.

Green roof on Chicago’s City Hall. Image: Conservation Design Forum/creative commons.

Cleaner, smarter cities

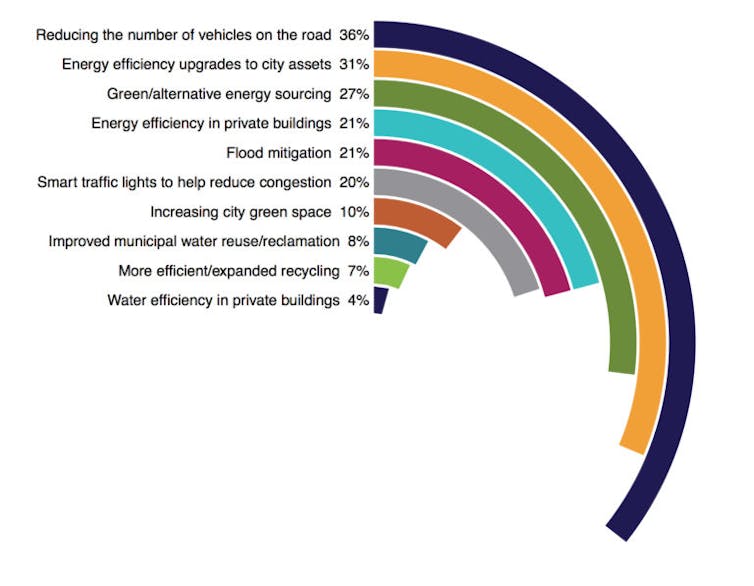

In our survey, mayors highlighted a number of environmental initiatives that they were interested in pursuing. Over one-third prioritised reducing the number of vehicles on the road and making city assets, such as buildings and vehicles, more energy-efficient.

Other popular programs included shifting toward green and alternative energy sources; promoting energy efficiency in private buildings; reducing risks of damage from flooding; and installing smart traffic lights that can change their own timing in response to traffic conditions. Many mayors are already implementing these initiatives in their communities.

When we asked mayors what would be required for a “serious and sustained effort to make a meaningful impact in my city” in combating climate change, they identified multiple programs. Large majorities agreed that significantly reducing their cities’ greenhouse gas emissions would involve steps such as requiring residents to change their driving patterns, increasing residential density, reallocating financial resources and updating building codes and municipal facilities.

Interestingly, mayors largely did not think that such initiatives would require imposing costly new regulations on the private sector. Only 25 per cent of mayors said such action was integral to addressing climate change.

Mayors’ top priorities for investments in the environment and sustainability. Image: BU Initiative on Cities/creative commons.

Climate politics is national and local

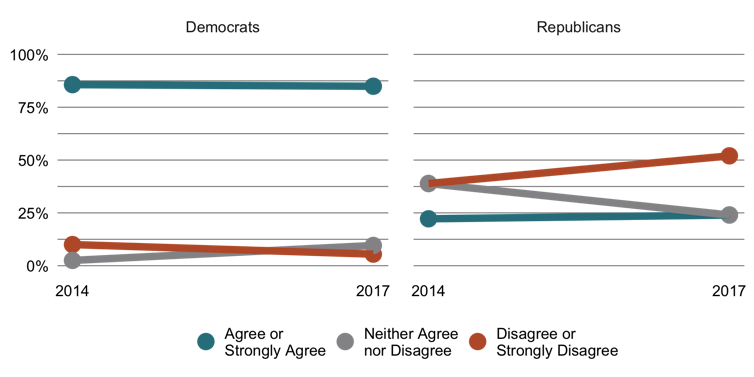

Mirroring national opinion, mayors’ views on climate change and environmental policy were sharply divided along partisan lines. While 95 per cent of the Democratic mayors we surveyed believed that climate change was a consequence of human activities, only 50 per cent of Republican mayors shared that view. And a mere 25 per cent of Republican mayors believe that mitigating climate change necessitated fiscal sacrifices, compared with 80 per cent of Democrats.

Interestingly, Republican views appear to have become more negative over time. When we surveyed mayors in 2014, just over one-third of Republicans did not believe that their cities should make significant financial expenditures to prepare for and mitigate impacts of climate change. By 2017, that figure had risen to 50 per cent. This shift suggests that Republicans are increasingly opposed to major policy initiatives targeting climate change, even at the local level.

However, despite these partisan differences, there was considerable consensus about making sustainability investments in cities, albeit perhaps for different motives. Democrats were were more likely to highlight green and alternative energy sources, and Republicans were more inclined towards smart traffic lights, but there was significant support across party lines for these kinds of improvements.

Mayors were asked how strongly they agreed with this statement: Cities should play a strong role in reducing the effects of climate change, even if it means sacrificing revenues and/or expending financial resources. Image: BU Initiative on Cities/creative commons.

A missed opportunity

President Trump’s strongest support in the 2016 election came from rural areas, and urban leaders have strongly opposed many of his administration’s proposals. We asked mayors about their ability to combat federal initiatives across an array of policies. Mayors identified two areas – policing and climate change – as opportunities where cities could do “a lot” to counteract Trump Administration policies.

Indeed, mayors have already banded together to send a strong political signal nationally, and perhaps even globally, on climate change. After President Trump abandoned the Paris climate agreement, many mayors publicly repudiated Trump and signed local commitments to pursue the accord’s goals. A large number of mayors have also more formally allied and joined city-to-city networks and compacts around climate change and other issues. Mayors see political value in these kinds of commitments. As one mayor put it, compacts “increase political voice… [it] give[s] more clout to an issue when mayors unite around common issues.”

![]() Almost two-thirds of the U.S. population lives in cities or incorporated places. While mayors and local governments cannot comprehensively tackle climate change alone, their sizeable political and economic clout may make them an important force in national and global sustainability initiatives. In our view, by not proposing substantial investment in infrastructure – including climate resilience in cities – the Trump administration is missing an opportunity to build better relationships with cities through steps that would benefit millions of Americans.

Almost two-thirds of the U.S. population lives in cities or incorporated places. While mayors and local governments cannot comprehensively tackle climate change alone, their sizeable political and economic clout may make them an important force in national and global sustainability initiatives. In our view, by not proposing substantial investment in infrastructure – including climate resilience in cities – the Trump administration is missing an opportunity to build better relationships with cities through steps that would benefit millions of Americans.

Katherine Levine Einstein, Assistant Professor, Political Science, Boston University; David Glick, Assistant Professor of Political Science, Boston University, and Maxwell Palmer, Assistant Professor of Political Science, Boston University.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.