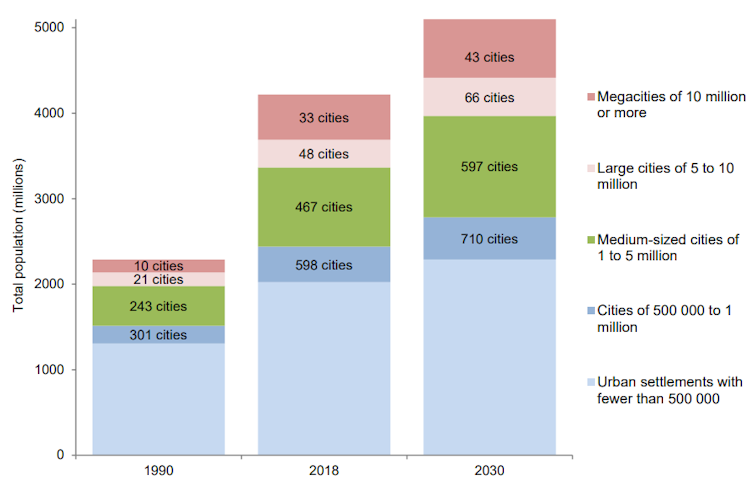

Some 60 per cent of the planet’s expected urban area by 2030 is yet to be built. This forecast highlights how rapidly the world’s people are becoming urban. Cities now occupy about 2 per cent of the world’s land area, but are home to about 55 per cent of the world’s people and generate more than 70 per cent of global GDP, plus the associated greenhouse gas emissions.

So what does this mean for people who live in the tropical zones, where 40 per cent of the world’s population lives? On current trends, this figure will rise to 50 per cent by 2050. With tropical economies growing some 20 per cent faster than the rest of the world, the result is a swift expansion of tropical cities.

Population and number of cities of the world, by size class, 1990, 2018 and 2030. Image: World Urbanization Prospects 2018, United Nations DESA Population Division.

The populations of these growing tropical cities already experience high temperatures made worse by high humidity. This means they are highly vulnerable to extreme heat events as a result of climate change.

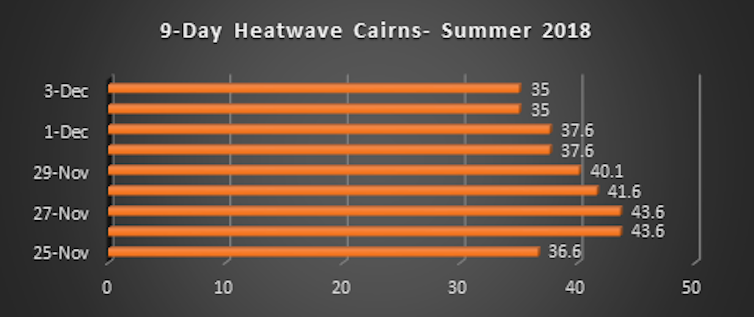

For example, extremely hot weather overwhelmed Cairns last summer. By December 3 2018, the city had recorded temperatures above 35°C nine days in a row. Four consecutive days were above 40°C.

Cairns’ heatwave summer. Image: authors, using BOM temperature data.

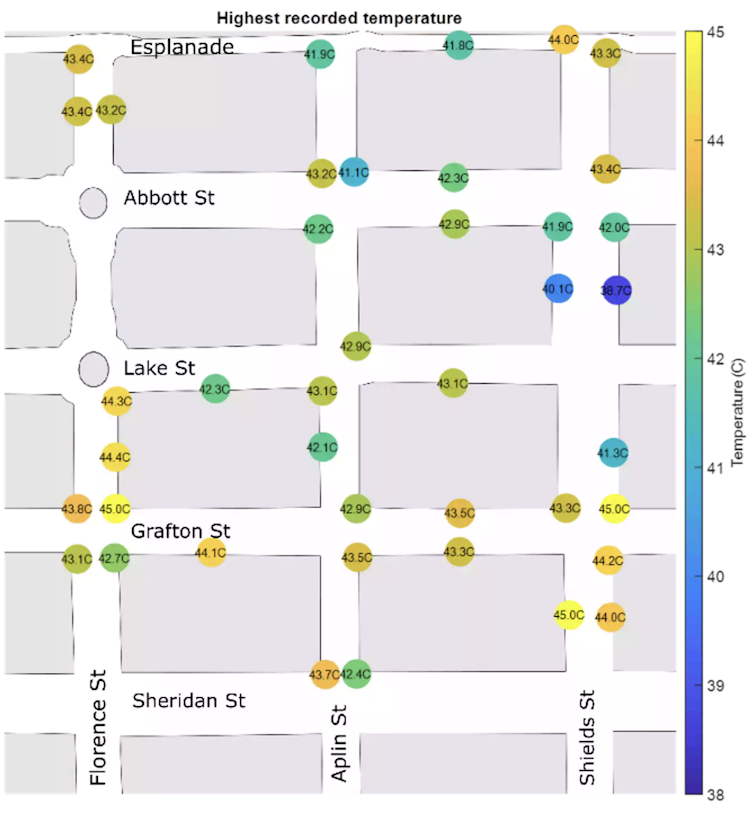

For our research, temperature and humidity sensors were strategically placed in the Cairns CBD to represent people’s experience of weather at street level. These recorded temperatures consistently higher than the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) recordings, reaching 45°C at some points.

Highest temperatures recorded by James Cook University weather data sensors during the November-December 2018 heatwave in Cairns. Image: Bronson Philippa/author provided.

Local effects magnify heatwave impacts

Urban environments in general are hotter than non-urbanised surroundings that are covered by vegetation. The trapping of heat in cities, known as the urban heat island effect, has impacts on human health, animal life, social events, tourism, water availability and business performance.

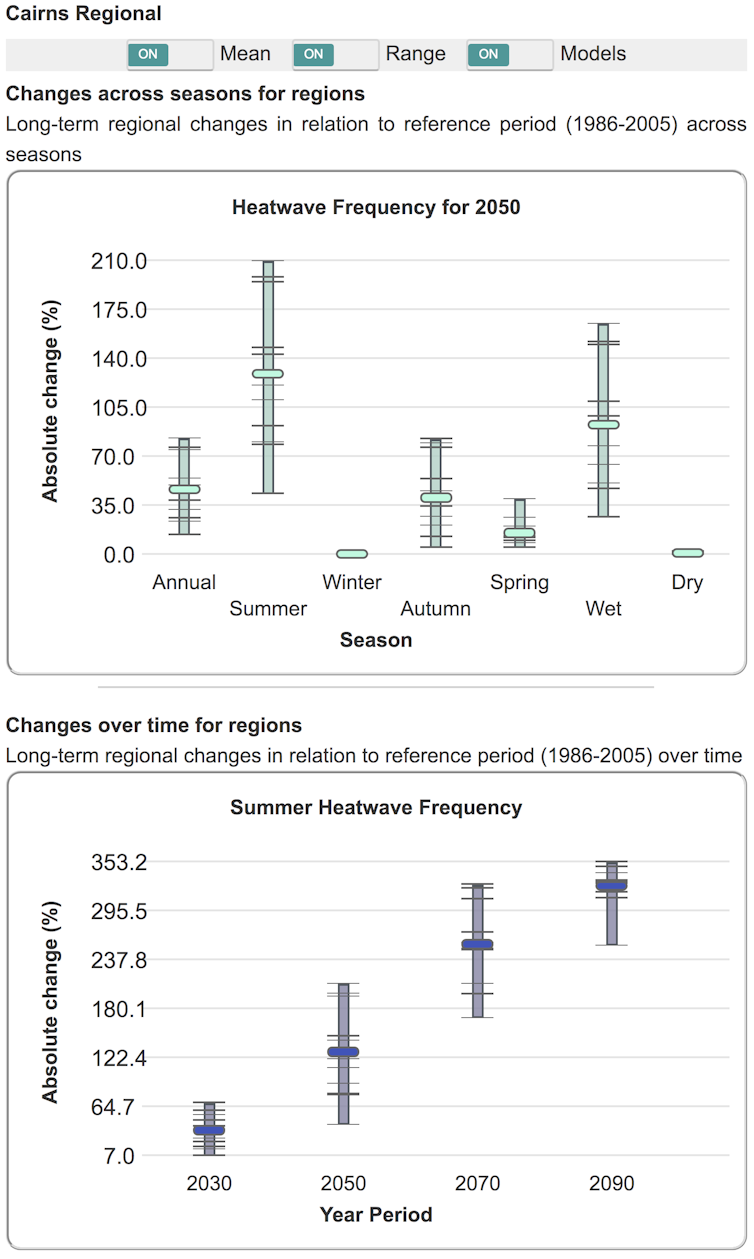

The urban heat island effect intensifies the impacts of increasing heatwaves on cities as a result of climate change.

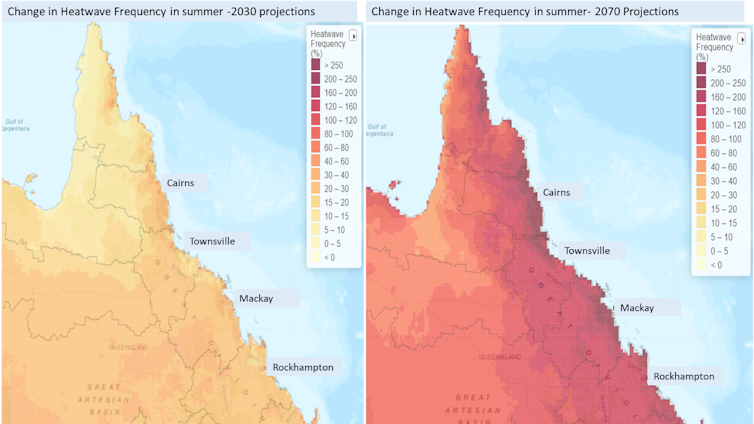

Projections of increased heatwave frequency for Cairns region using visualisation platform on Queensland Future Climate Dashboard. Image: Queensland Future Climate Dashboard/Queensland Government.

But it is important to remember that other local factors also influence these impacts. These include the scale, shape, materials, composition and growth of the built environment in a particular location and its surrounding areas.

The differences between the BoM data recorded at Cairns airport and the inner-city recordings show the impacts of urban expansion patterns, built form and choice of materials in tropical cities.

On one hand, Cairns’s linear layout has enabled the formation of attractive places for commercial activities. As these activity centres evolve into focal points of urban life, they in turn influence all sorts of socioeconomic parameters.

On the other hand, the form the built environment takes changes the patterns of wind, sun and shade. These changes alter the urban microclimate by trapping heat and slowing or channelling air movements.

The layout and structures of Cairns CBD alter local microclimates by trapping heat and altering air flows. Image: State of Queensland 2019.

Shifting the focus to the tropics

To date, a large body of research has explored the undesired consequences of climate change and urban heat islands. However, the focus has been on capital and metropolitan cities with humid continental climates. Not many studies have looked at the economic and social impacts in the tropical context, where hot and humid conditions create extra heat stress.

Add the combined effects of climate change and urban heat islands and what are the socio-economic consequences of heatwaves in a tropical city like Cairns? We see that climate change adds another dimension to the relationship between cities, economic growth and development.

This presents a huge opportunity to start thinking about building cities that are not superficially greenwashed, but which instead tackle pressing issues such as climate variability and create sustainable business and social destinations.

In cold climates, heatwaves and urban heat islands are not necessarily undesired, but their negative impacts are more obvious and harmful in warmer climates. And these harmful impacts of heatwaves on our economy, environment and society are on the rise.

We have scientific evidence of the increasing length, frequency and intensity of heatwaves. The number of record hot days in Australia has doubled in the past five decades.

Projections of changes in heatwave frequency for northern Queensland in 2030 and 2070. Image: Queensland Future Climate Dashboard/Queensland Government.

What are the costs of heatwaves?

Increased exposure to heatwaves amplifies the adverse economic impacts on industries that are reliant on the health of their outdoor workers. This is in addition to the extreme heat-related fatalities and healthcare costs of heatwave-related medical emergencies. As a PwC report to the Commonwealth on extreme heat events stated:

Heatwaves kill more Australians than any other natural disaster. They have received far less public attention than cyclones, floods or bushfires — they are private, silent deaths, which only hit the media when morgues reach capacity or infrastructure fails.

Heat also has direct impact on economic production. A 2010 study found a 1°C increase resulted in a 2.4 per cent reduction in non-agricultural production and a 0.1 per cent reduction in agricultural production in 28 Caribbean-basin countries. Another study in 2012 found an 8 per cent weekly loss of production when the temperature exceeded 32°C for six days in a row.

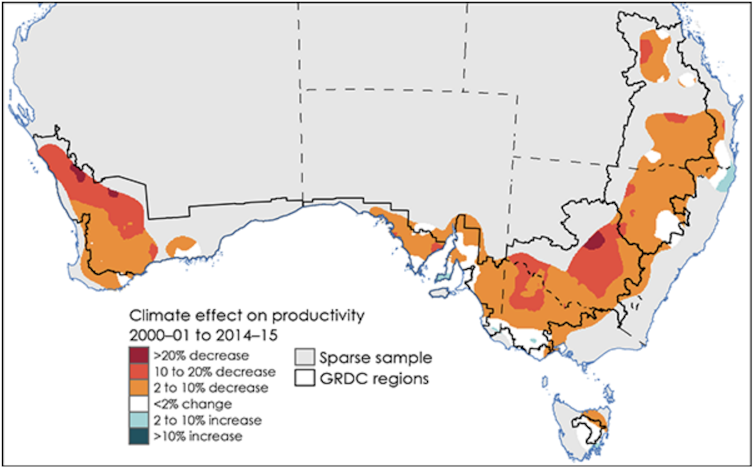

The 2017 Farm performance and climate report by the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES) states:

The recent changes in climate have had a significant negative effect on the productivity of Australian cropping farms, particularly in southwestern Australia and southeastern Australia.

Average climate effect on productivity of cropping farms in southwestern and southeastern Australia since 2000–01 (relative to average conditions from 1914–15 to 2014–15). Image: Farm performance and climate, ABARES.

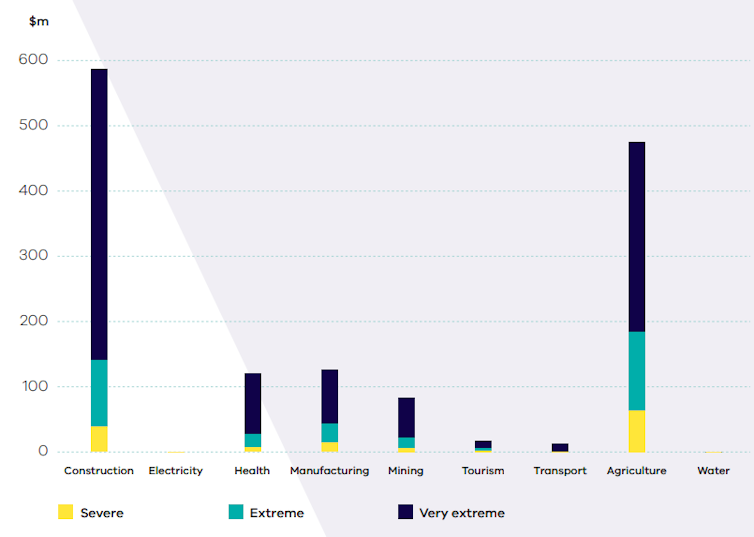

It’s not just farming that is vulnerable. A Victorian government report report this year estimated an extreme heatwave event costs the state’s construction sector A$103 million. The impact of heatwaves on the city of Melbourne’s economy is estimated at A$52.9 million a year on average.

Impacts of heatwaves on Victoria’s main economic sectors. Image: State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning.

According to this report, economic costs increase exponentially as the severity of heatwaves increases. This has obvious implications for cities in tropical regions.

As the next step in our research, we are examining the relationship between local urban features, urban heat islands, the resulting city temperatures and their direct and indirect (spillover) effects on local and regional economic activities.

This article by Taha Chaiechi, Senior Lecturer, James Cook University and Silvia Tavares, Lecturer in Urban Design, James Cook University, is republished from The Conversation.