Around the world, cities endeavour to cut greenhouse gas emissions, while adapting to the threats – and opportunities – presented by climate change. It’s no easy task, but the first step is to make a plan outlining how to meet the targets set out in the Paris Agreement, and help limit the world’s mean temperature rise to less than two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

About 74 per cent of Europe’s population lives in cities, and urban settlements account for 60-80 per cent of carbon emissions – so it makes sense to plan at an urban level. Working to meet carbon reduction targets can also reduce local pollution and increase energy efficiency – which benefits both businesses and residents.

But it’s just as important for cities to adapt to climate change – even if the human race were to cut emissions entirely, we would still be facing the extreme effects of climate change for decades to come, because of the increased carbon input that has already taken place since the industrial revolution.

In the most comprehensive survey to date, we collaborated with 30 researchers across Europe to investigate the availability and content of local climate plans for 885 European cities, across all 28 EU member states. The inventory provides a big-picture overview of where EU cities stand, in terms of mitigating and adapting to climate change.

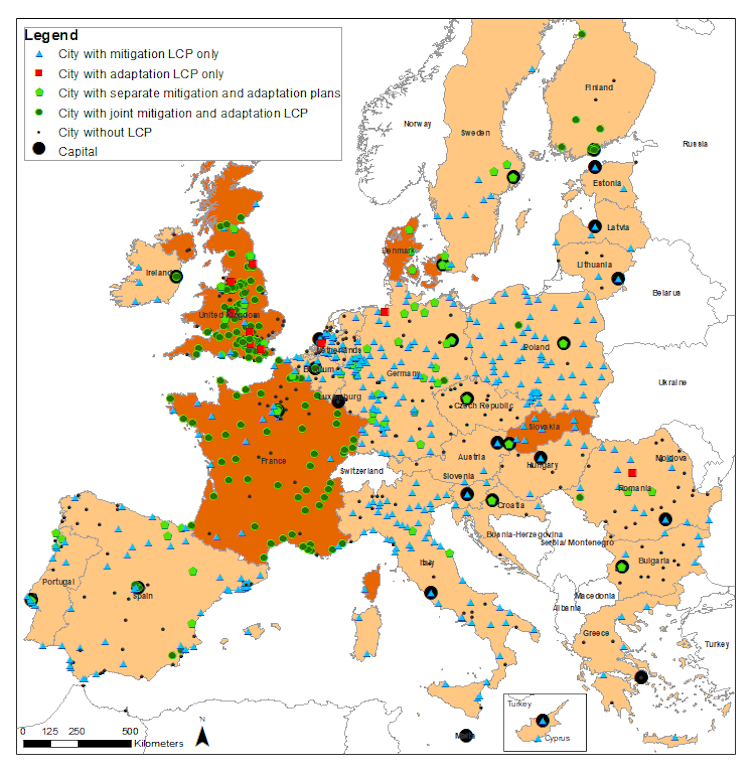

Map of cities with local climate plans (LPCs). The countries in dark orange make it compulsory to have local climate plans. Image: author provided.

The leaderboard

The good news is that 66 per cent of EU cities have a mitigation or adaptation plan in place. The top countries were Poland – where 97 per cent of cities have mitigation plans – Germany (81%), Ireland (80 per cent), Finland (78 per cent) and Sweden (77 per cent). In Finland, 78 per cent of cities also had a plan for adapting to climate change.

But only a minority of EU countries – including Denmark, France, Slovakia and the UK – have made it compulsory for cities to develop local climate plans. In these countries, cities are nearly twice as likely to have a mitigation plan and five times as likely to have an adaptation plan. Throughout the rest of the EU, it is mainly large cities that have local climate plans.

There were some shortcomings worth noting: 33 per cent of EU cities (that’s 288 cities) have no standalone climate plans whatsoever – including Athens (Greece), Salzburg (Austria), and Palma de Mallorca (Spain). And not one city in Bulgaria or Hungary has a standalone climate plan. Only 16 per cent of cities – that’s a total of 144 – have joined-up mitigation and adaptation plans, and most of these were in France and the UK – though cities such as Brussels (Belgium), Helsinki (Finland) and Bonn (Germany) had joined-up plans as well.

Some cities have made climate initiatives a common feature in planning activities, often aiming for broader environmental goals, such as resilience and sustainability. Some of these forward-looking cities – Rotterdam and Gouda in the Netherlands, for example – may not have standalone climate change mitigation or adaptation plans, per se. Instead, climate issues are integrated into broader development strategies, as also seen in Norwich, Swansea, Plymouth and Doncaster in the UK.

Mitigation, adaptation – or both?

Plans for mitigating the effects of climate change are generally straightforward: they look at ways to increase efficiency, transition to clean energy and improve heating, insulation and transport. In doing so, they are likely to result in financial savings or health benefits for the municipality, and the public. For example, more low-emission vehicles on the road doesn’t just mean less carbon emissions – it also means better air quality for the city’s residents.

Adapting to climate change is not always so simple. Each area will need to adapt in different ways. Some adaptations – such as flood defences – can require huge investment to build, and only rarely prove their effectiveness. Yet there are plans and measures that cities can take, to both mitigate the threats from climate change and adapt to the changes that are already coming.

One way for cities to become more resilient to climate change is to integrate infrastructures for energy, transport, water and food, and allow them to combine their resources. A sensors become more commonplace across European cities, it’s easier to monitor the impacts of local plans to reduce emissions and stay on top of extreme weather. The University of Newcastle in the UK is home to the Urban Observatory, which provides one of the largest open-source digital urban sensing networks in the world.

Spot the sensor. Image: author provided.

Across the board, cities need to improve the way they manage water at the surface and below ground. Installing more green features in city centres or strategic locations can help urban areas adapt to heatwaves, extreme rainfall and droughts all at once. To find out what works and what doesn’t, it’s essential for cities to network and share knowledge, to create and improve on their local climate plans.

There is simply too much at stake for the world’s cities to go their separate ways when it comes to climate change. We have found that international climate networks make a big difference to countries and cities, as they develop and implement their climate plans. For instance, 333 EU cities of our sample are signatories of the Covenant of Mayors and through that are given support and encouragement as they engage in climate change planning and action.

Our study shows that cities are taking climate change threats seriously, but there is clearly more work to be done. It is a near certainty that if cities do not plan and act now to address climate change, they could find themselves in a far more precarious position in the future.

![]() While there is plenty that cities can do, national governments must still take the lead – providing legal and regulatory frameworks and guidance. Our study has demonstrated that this is one of the most effective ways to make sure that cities – and their citizens – are well prepared for the threats and opportunities that climate change will bring.

While there is plenty that cities can do, national governments must still take the lead – providing legal and regulatory frameworks and guidance. Our study has demonstrated that this is one of the most effective ways to make sure that cities – and their citizens – are well prepared for the threats and opportunities that climate change will bring.

Oliver Heidrich, Senior Researcher in Urban Resource Modelling, Newcastle University and Diana Reckien, Associate Professor for Climate Change and Urban Inequalities, University of Twente.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.