If recent trends continue for another two years, the global share of electricity from renewables excluding hydropower will overtake nuclear for the first time. Even 20 years ago, this nuclear decline would have greatly surprised many people – particularly now that reducing carbon emissions is at the top of the political agenda.

On one level this is a story about changes in relative costs. The costs of solar and wind have plunged while nuclear has become almost astoundingly expensive. But this raises the question of why this came about. As I argue in my new book, Low Carbon Politics, it helps to dip into cultural theory.

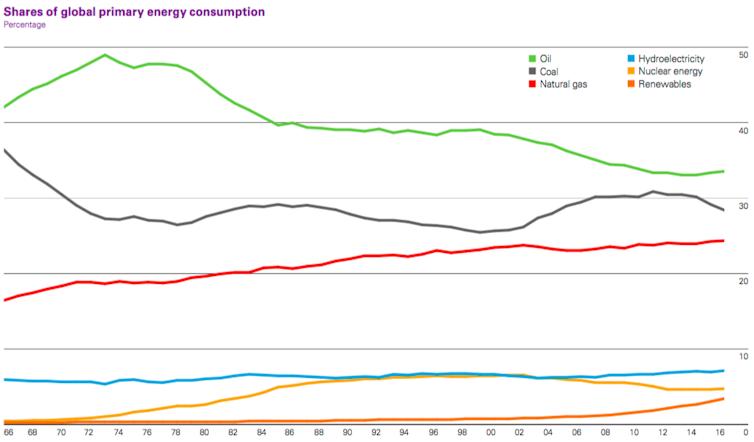

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy, June 2017.

Culture wars

The seminal text in this field, Risk and Culture (1982), by the British anthropologist Mary Douglas and American political scientist Aaron Wildavsky, argues the behaviour of individuals and institutions can be explained by four different biases:

- Individualists: people biased towards outcomes that result from competitive arrangements;

- Hierarchists: those who prefer ordered decisions being made by leaders and followed by others;

- Egalitarians: people who favour equality and grassroots decision-making and pursue a common cause;

- Fatalists: those who see decision-making as capricious and feel unable to influence outcomes.

The first three categories help explain different actors in the electricity industry. For governments and centralised monopolies often owned by the state, read hierarchists. For green campaigning organisations, read egalitarians, while free-market-minded private companies fit the individualist bias.

The priorities of these groups have not greatly changed in recent years. Hierarchists tend to favour nuclear power, since big power stations make for more straightforward grid planning, and nuclear power complements nuclear weapons capabilities considered important for national security.

Egalitarians like Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth usually oppose new nuclear power plant and favour renewables. Traditionally they have worried about radioactive environmental damage and nuclear proliferation. Individualists, meanwhile, favour whichever technologies reduce costs.

These cultural realities lie behind the problems experienced by nuclear power. To compound green opposition, many of nuclear power’s strongest supporters are conservative hierarchists who are either sceptical about the need to reduce carbon emissions or treat it as a low priority. Hence they are often unable or unwilling to mobilise climate change arguments to support nuclear, which has made it harder to persuade egalitarians to get on board.

This has had several consequences. Green groups won subsidies for renewable technologies by persuading more liberal hierarchists that they had to address climate change – witness the big push by Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth for the feed-in tariffs that drove solar uptake in the late 2000s, for example. In turn, both wind and solar have been optimised and their costs have come down.

Nuclear largely missed out on these carbon-reducing subsidies. Worse, greens groups persuaded governments as far back as the 1970s that safety standards around nuclear power stations needed to improve. This more than anything drove up costs.

As for the individualists, they used to be generally unconvinced by renewable energy and sceptical of environmental opposition to nuclear. But as relative costs have changed, they have increasingly switched positions.

The hierarchists are still able to use monopoly electricity organisations to support nuclear power, but individualists are increasingly pressuring them to make these markets more competitive so that they can invest in renewables more easily. In effect, we are now seeing an egalitarian-individualist alliance against the conservative hierarchists.

Both sides of the pond

Donald Trump’s administration in the US, for example, has sought subsidies to keep existing coal and nuclear power stations running. This is both out of concern for national security and to support traditional centralised industrial corporations – classic hierarchist thinking.

Yet this has played out badly with individualist corporations pushing renewables. Trump’s plans have even been rejected by some of his own appointments on the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

In similarly hierarchist fashion, electricity supply monopolies in Georgia and South Carolina started building new nuclear power stations after regulatory agencies allowed them to collect mandatory payments from electricity consumers to cover costs at the same time.

Yet even hierarchists cannot ignore economic reality entirely. The South Carolina project has been abandoned and the Georgia project only survives through a very large federal loan bailout.

Contrast this with casino complexes in Nevada like MGM Resorts not only installing their own solar photovoltaic arrays but paying many millions of dollars to opt out from the local monopoly electricity supplier. They have campaigned successfully to win a state referendum supporting electricity liberalisation.

Casino solar, Las Vegas. Image: author provided.

The UK, meanwhile, is an example of how different biases can compete. Policy has traditionally been formed in hierarchical style, with big companies producing policy proposals which go out to wider consultation. It’s a cultural bias that favours nuclear power, but this conflicts with a key priority dating back to Thatcher that technological winners are chosen by the market.

This has led policymakers in Whitehall to favour both renewables and nuclear, but the private electricity companies have mostly refused to invest in nuclear, seeing it as too risky and expensive. The only companies prepared to plug the gap have been more hierarchists – EDF, which is majority-owned by France, and Chinese state nuclear corporations.

Even then, getting Hinkley C in south-west England underway – the first new nuclear plant since the 1990s – required an extensive commitment by the UK treasury to underwrite bank loans. There is also an embarrassingly high price to be paid for the electricity over a very long 35-year period. Such has been the bad publicity that it’s hard to imagine a politician agreeing to more plant on such terms.

Where does this reality leave hierarchists? Increasingly having to explain prohibitive nuclear costs to their electorates – at least in democracies. The alternative, as renewable energy becomes the new orthodoxy, is to embrace it.

In Australia, for example, a big utility company called AGL is trying to seduce homeowners to agree to link their solar panels to the company’s systems to centralise power dispatch in a so-called a “virtual power plant”.

![]() When the facts change, to misquote John Maynard Keynes, you can always change your mind.

When the facts change, to misquote John Maynard Keynes, you can always change your mind.

David Toke, Reader in Energy Policy, University of Aberdeen.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.